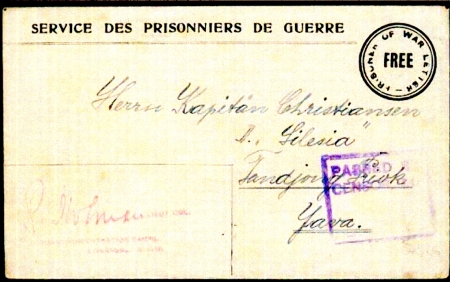

This SERVICE DES PRISONNIERS DE GUERRE stampless FREE cover [Emery Type 3] was addressed to Herrn Kapitan Christiansen “Silesia”, Tandjong Priok, Yava, and it had a red authorizing signature cachet of Lieutenant Colonel Holman at Liverpool N.S.W. [Emery CA 232] as well as a boxed violet PASSED BY/ CENSOR/ S.D. [C.M. 43] (Figure 1).

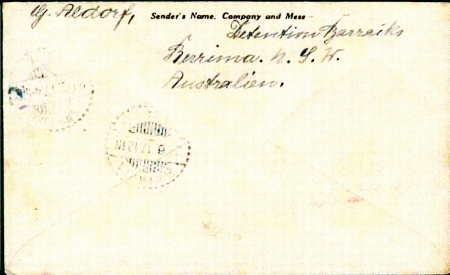

The reverse showed the sender’s name and address: G. Aldorf, Detention Barracks, Berrima, N.S.W., Australien. There were two typical Netherlands East Indies cancels, one which showed a definite BATAVIA/ 20.8.17.12 (–) N and the other may possibly have been for Tandong Priok (Figure 2).

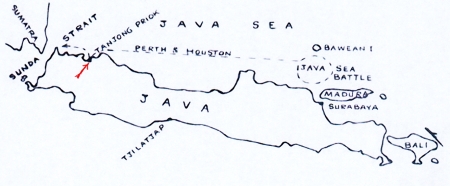

Tandjong Priok is one of 2 ports on the west side of the north coast of Java and serves as the Port of Batavia, now Djkarta. The port was started in 1914 and construction was continued into 1925. Its position is shown in a drawing of a naval battle in the area during February-March 1942, and Batavia (not shown) is inland and south of Tandjong Priok (Figure 3).

There were 2 ships by the name S.S. Silesia and the original sailed in the second half of the 19th century mainly with immigrants from Hamburg to New York, but this was not the steamship named on this cover. There are 2 references to the second S.S. Silesia during WW2 and it was used as a troop ship, as well as for rescuing POWs and civilian internees gathered in the Dutch East Indies. No picture of this ship or additional details have been found.

The disused sandstone gaol in the Southern Highlands town of Berrima, N.S.W. was reopened in 1914 as an interment camp for German internees and prisoners of war. The 400 or so residents were made up of German ship’s officers and sailors who had been in Australia at the outbreak of WW I, prisoners of war taken from the SMS Emden after its battle with the HMAS Sydney, and other Germans deported from British colonies.

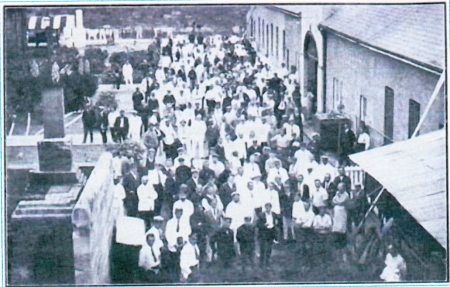

The internees lived in the stone gaol cells and additional barracks, but were allowed to move about freely within a two-mile radius of the gaol during the day. The main entrance to the gaol with a line of guards on either side of the driveway is seen Figure 4.

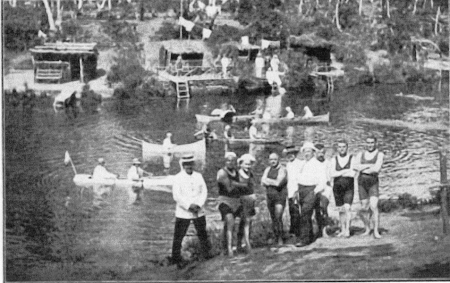

They were allowed to build small wooden huts from the local trees, and grow flowers and vegetables on the banks of the nearby Wingecaribbee River, which provided a popular recreation area. The Berrima camp was closed in 1919 after the end of World War I. The photos show a roll call of the internees at Berrima, as well as boating and swimming on the Wingecaribee river, with the huts seen on the opposite bank (Figures 5 & 6).

The outbreak of fighting in Europe in August 1914 immediately brought Australia into the ‘Great War’. Within one week of the declaration of war all German subjects in Australia were declared ‘enemy aliens’ and were required to report and notify the Government of their address. In February 1915 enemy aliens were interned either voluntarily or on an enforced basis. In New South Wales the principal place of internment was the Holsworthy Military Camp where between 4,000 and 5,000 men were detained. Women and children of German and Austrian descent detained by the British in Asia were interned at Bourke and later at Molonglo near Canberra. Former gaols were also used. Men were interned at Berrima Gaol (constructed 1840s) and Trial Bay Gaol (constructed 1889). At these camps the internees organised themselves into arts and craft societies and produced large German events and festivals to pass their time, and to retain a sense of identity.

The internees were allowed a large degree of freedom and self-organisation by the Camp authorities. The regimented and structured nature of Navy culture resulted in the Berrima internees being largely self regulating and self-managing. The internees also found a welcoming community as some of the families in the area were descended from German settlers who came to the district in the 1840s. Despite the anti-German diatribes from mainstream media, the Berrima residents warmed to the internees who purchased bread and meat from local shops, thus bolstering the local economy. The internees helped local residents to rescue animals, fight bush fires and deal with unwanted snakes in their houses. The local residents helped the internees to gain everyday items but commodities such as newspapers were banned. Given the biased nature of the Australian media, the internees preferred to get their newspapers from neutral countries.

This idyllic setting did not live up to the expectations of the internees, as evidenced by their complaints to the Swedish authorities (who as neutrals had access to the internees). The Commonwealth rebuttal to their complaints can be found in a file held by the Governor-General’s Office in 1918. The Governor-General at that time (from May 1914 to October 1920) was Sir Ronald Craufurd and the frontispiece of the rebuttal is seen in Figure 7.

The internees complaints, except for health issues, were not listed, and what follows is only an abbreviated description of the rebuttal: “The camp is situated in the healthiest climate of New South Wales. The internees are allowed liberty to wander about in any direction within two miles of the camp and their general health is excellent. There is a hospital in Berrima and at least one Army Medical Corps Orderly in attendance. The Medical Officer …. visits the camp regularly once a week and is available at any other time as required …..The question of referring a German doctor from one of the other camps has received careful consideration. There are very few doctors interned … and it has been decided that the transfer of any of the medical men who are interned could not be allowed.”